“People wanted a transcontinental railroad. This was because it was absolutely necessary to bind the country together. Further, it was possible, because train technology was improving daily. The locomotives were getting faster, safer, more powerful, as the cars became more comfortable..”

– Nothing Like It In The World by Stephen Ambrose

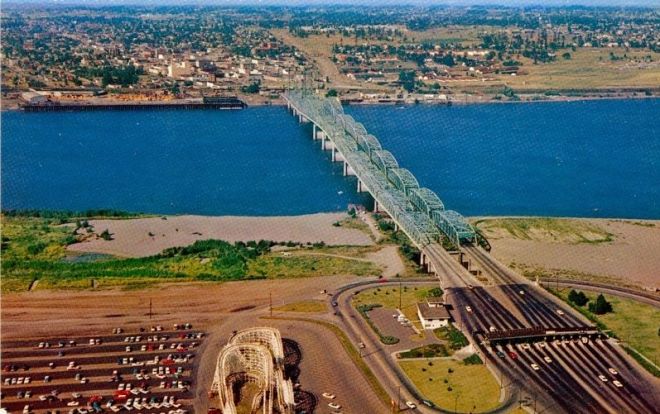

The Interstate Bridge has a total length of 3,538 ft, with 72 ft clearance at its highest fixed span and 176 ft at it’s highest lift clearance. Today the Interstate Bridge is congested, routinely backing up traffic for miles. More than 130,000 vehicles cross the I-5/Columbia River bridge, daily.

The crew must lift the I-5 Bridge when a vessel needs the clearance, with the exception of closure periods from 6:30 to 9 a.m. and 2:30 to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday. Nearly ALL the vessel traffic goes under the bridge without a lift.

The recent 600-ft wide, 43-ft deep navigation channel terminates at the Interstate Bridge. The I-5 bridges were designed with an assumed life of 50 years. But average bridge life in Oregon is 85 years. According to state officials, 1,500 Oregon bridges will reach the end of their service life by 2020.

KGW’s Pat Dooris reports the I-5 bridge funding is taking clearer shape, even as design hits river clearance concerns.

HISTORY

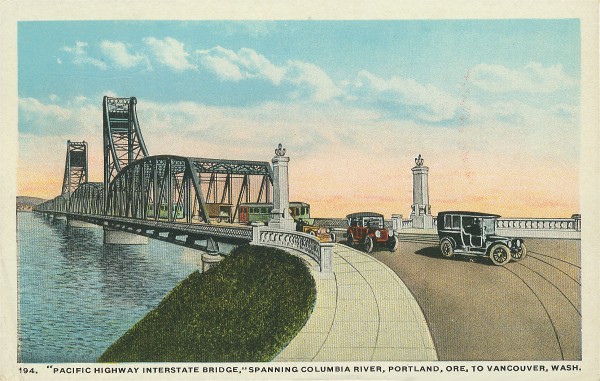

According to Vintage Portland, the Interstate Bridge, linking Oregon and Washington, was dedicated on February 14, 1917, as a single bridge with two-way traffic.

The 1905 Expo in Portland caused a massive traffic jam at the Columbia River steam ferry, which sparked widespread demand for a bridge. John Switzler ran the Portland – Vancouver ferry before the construction of the Interstate Bridge.

By 1914, with a great deal of bi-state local support, the Washington and Oregon state legislatures approved the sale of bonds to fund the Interstate Bridge. The original bridge cost a little under $1,790,000 with Clark County voting overwhelmingly for the issuance of $500,000 of bonds and Multnomah County issuing bonds for $1,250,000.

On December 30, 1916, the Interstate Bridge opened to foot traffic due to bad weather and ice on the Columbia preventing the ferry from running.

On January 24, 1917, a streetcar made a trial run over the new bridge. Streetcars had regular schedules between Vancouver and Portland, and continued until 1940 when asphalt was poured over the tracks. For the first 25 years (between 1907-1932), streetcars were the dominant mode of transit.

Here’s a century of transportation charted by Bike Portland. Automobiles didn’t begin to dominate Portland transportation until the 1940s.

The 100th anniversary of the I-5 Bridge was celebrated Saturday February 11th, 2017 from 3:00pm – 6:00pm at the Red Lion on the River – Jantzen Beach.

JOHN BARBER, who teaches Vancouver’s Digital Media at WSU (Facebook), premiered a remarkable re-creation of the 1917 ceremonies.

John’s A Mighty Span broadcast re-creation is a 15:00 sound installation invited by the PDX Bridge Festival.

This 1917 view of the bridge shows the earlier passenger ferry, shot from the Vancouver side.

Located at River Mile 106.5, the original bridge is 3,531 ft long with the lift span between towers 250 ft wide and 150 ft high above ordinary high water. The interstate Bridge originally had a toll of 5 cents for motorists and people riding animals. The toll ended in 1929.

Two little girls in white stockings and high button shoes pulled loose the bow that opened the first bridge. The same pair, 41 years older, untied the bow that opened the new $6,815,000 span in 1958. Tolls for the 1958 bridge of 20 cents were collected until 1966.

When the 1958 span was constructed, the bridge was modified to include an arch in the center span to allow most barge traffic to pass under without requiring a lift. When the new span opened in 1958, the original bridge was closed for two years to add a matching humped section.

The original (East bridge) incorporated trolley tracks. The bridge is consequently heavier and has larger counter-weights on the lift section. The original northbound bridge weighs about a third more than the newer one.

Vancouver’s interstate bridge assembly yard built the bridge sections which were then ferried into place.

In the 1920s, Jantzen Knitting Mills built the 112-acre Jantzen Beach Amusement Park as a promotion for Jantzen swimming suits. It had swimming pools, roller coasters, ballrooms, and the C.W. Parker merry-go-round.

Attractions like the Jantzen Beach Amusement Park, Oaks Park, and the Council Crest Amusement Park also worked as promotions for Portland Streetcars. In 1970, the Jantzen Beach Park closed its doors, the buildings were demolished, and the site redeveloped into the Jantzen Beach Center Mall.

The Interstate Bridge has been found to have significant seismic vulnerabilities and would collapse or be rendered unusable in an earthquake, according to ODOT’s Seismic Report on bridges. Bruce Johnson, state bridge engineer for the O-DOT, says of the Interstate Bridge, “I’m confident that it would collapse under a 9.0 earthquake”.

The lift span on the older (eastern) bridge has a cracked trunnion, an axle pulley that will cost as much as $12 million to fix in a few years, reports The Oregonian. A 10-man Oregon crew currently maintains and operates the bridge, headed by bridge supervisor Marc Gross. Bridge tenders on Gross’s crew man the drawbridge controls around the clock, performing about 400 lifts a year.

The Vancouver streetcar was owned by Portland Railway, Light and Power Company (now PGE). It carried passengers from Vancouver WA, across the Columbia River (via the interstate bridge) to Hayden Island where it split into two directions. One line continued south towards downtown Portland.

The other line veered diagonally, southeast across the North Portland harbor over a 1700 foot long wooden trestle and stopped at a station known as Faloma on the Oregon shore, the gateway to the Lotus Isle resort. The Tomahawk Island bridge crossed North Portland Harbor.

You can still see the RR bridge pilings near Lotus Isle Park.

The city park is located on what was once called Sand Island. The 1938 map (below) shows the still separated “Sand Island” where the Lotus Isle Amusement Park was located.

Sand Island was later renamed Tomahawk Island (after someone found a tomahawk), and eventually merged with Hayden Island with infill when the I-5 freeway was built in the 1960s. Hayden Island Drive was originally constructed in the early 1970s, and was rebuilt in the mid 1980s due to settlement failure.

Hayden Island has held a series of names. It was first recorded as Menzies Island in 1792 by British Lt. Broughton. Lewis and Clark called it “Image Canoe Island” in 1905 for an impressively carved canoe they encountered while camping there. Finally it was renamed for Guy Hayden, an early mayor of Vancouver who owned a farm on the island. Hi-Noon has additional history of the island.

The Columbia River Railroad Bridge, about a mile West of the Interstate Bridge, is owned and operated by BNSF Railway. Completed in 1908, it was the first bridge of any kind to be built across the lower Columbia River. It preceded the nearby Interstate Bridge by almost nine years. The same RR bridge remains in use today.

Abraham Lincoln signed the Northern Pacific Charter in 1864 with the charge of constructing a rail connection between the Great Lakes and Puget Sound. In 1873 the Northern Pacific announced that Tacoma, Washington would be the railroad’s terminus on Puget Sound and scheduled service began between Kalama and Tacoma in January 1874.

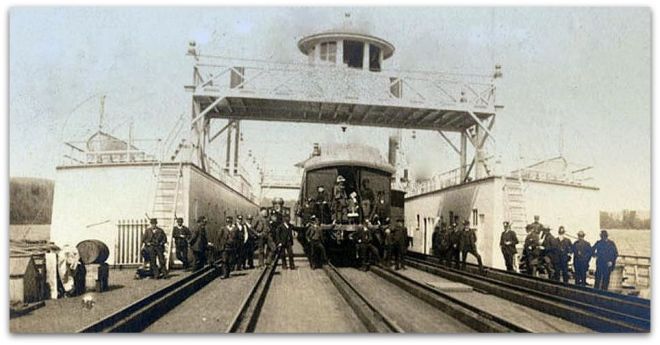

Before the 1908 Railroad Bridge in Portland, the Northern Pacific built a railroad ferry that connected the Port of Kalama on the Washington side to Goble Oregon, just east of Longview/Rainier. Passenger service continued until 1934.

The Goble train ferry began in 1884 and continued until 1908 (when the Portland RR bridge was completed). The mighty Tacoma was built in Delaware but disassembled, boxed and shipped off to Oregon. Some 57,159 separate pieces were brought out from New York by the Tillie E. Starbuck, the first iron sailing vessel built in the United States, and reassembled in Portland to build the train ferry.

The Pacific Northwest Rail Corridor is one of eleven federally designated high-speed rail corridors in the United States. The 466-mile corridor extends from Eugene, Oregon to Vancouver, British Columbia via Portland and Seattle.

The North Portland Peninsula railroad tunnel, near N Columbia Blvd (north portal), shortens freight movement north over the Columbia River to Washington State. The Kenton Line feeds UP traffic (in red) to the Port of Portland. BNSF tracks are north of the Columbia River, while UP tracks are on the south side.

The Astoria-Megler Bridge turned 50 last summer. The 4.1 mile bridge was the last segment of US Route 101 between Olympia and Los Angeles. As of 2004, an average of 7,100 vehicles per day use the Astoria–Megler Bridge. Construction started on Nov 5, 1962.

On August 27, 1966, with more than 30,000 people in attendance, Governors Mark Hatfield of Oregon and Dan Evans of Washington opened the bridge by cutting a ceremonial ribbon. It has 196 ft ship clearance in the channel and cost $24 million, paid for by tolls until 1993. There’s a great video on the Astoria-Megler50.com website.

Interstate 5 Bridge on Columbia River #theta360 – Spherical Image – RICOH THETA

Some say the I-5 bridge is haunted by the ghost of Vancouver Mayor Percival who may – or may not – have taken his life shortly after the bridge was dedicated. “The story goes that people will be driving across the bridge at night, and they’ll see this tall, slender man walking in period clothing,” according to Brad Richardson, a historian and volunteer services coordinator with the Clark County Historical Museum. “It’s always on fall nights, and it’s always on the old (parts) of the bridge.”

The Vancouver Waterfront Project will span most of the vacant land between the Interstate 5 Bridge, top, and the BNSF Railway bridge.

Here are 360 degree photos of the I-5 bridge on Flickr. Click on them to see “VR” panoramas.

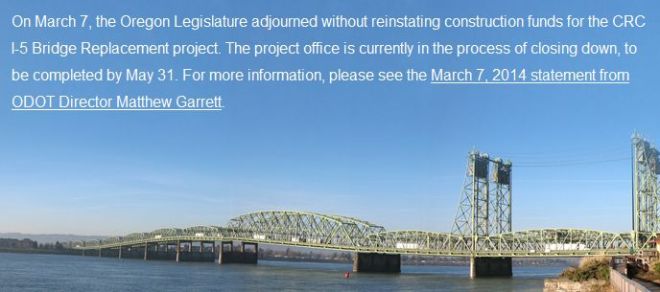

Columbia River Crossing would have replaced the obsolete four-lane Interstate 5 bridge with a new 12-lane bridge and light-rail extension over the Columbia River. That project, 10 years in planning, is now officially dead. Here’s a Bloomberg story on our (non-happening) bridge.

Portland-Vancouver drivers can anticipate almost 10 hours of congested travel a day by 2020, compared to a total of four hours of congested travel today. Because the Port of Portland lost their container shipping business on Terminal 6, additional truck traffic is also expected. Approximately $40 billion in freight crosses the I-5 bridge annually.

The existing freeway would have been replaced by a 17-lane behemoth, 45-feet high and 450-feet-wide. The original 2013 proposal, which was rejected, had a $3.5 billion price tag, which included light rail accommodations. Slightly more than half of that money — $1.8 billion — was to come from tolls. The federal government and the two state governments were to split the remaining costs, with the project dying when Washington’s Senate would not provide the state’s $450 million share.

CRC planners initially drew up a fixed span with just 95 feet of clearance over the Columbia River. That height was rejected by the U.S. Coast Guard and others as inadequate for the navigation and economic needs of river users. Here’s the Coast Guard Statement of Facts.

The project was subsequently redesigned to a height of 116 feet, and riverfront companies harmed by a 116-foot span made mitigation deals with the CRC.

Most of the I-5 congestion is on the Oregon side but largely caused by Vancouver commuters. Washington didn’t want to pay for Oregon road work. A lack of cooperation and common courtesy killed it.

Portlanders say many ‘Couverites use Oregon roads and parks, then drive home to their Clark County homes, paying no Oregon taxes or Washington state income tax’. Clark County’s population nearly doubled from 238,000 in 1990 to more than 400,000 today.

CRC detractors said the light rail component should be removed. They believed Tri-Met would siphon business away from the downtown area to the sales tax free haven on Jantzen Beach and Portland.

CRC supporters said the $850 million in federal transit funding was a necessary component. Never mind that Light Rail would likely have given a big boost for Vancouver’s Waterfront project and probably the city’s economy.

The project was considered dead after Washington lawmakers failed to fund their $450 million share of the $3.4B project in June, 2013, but became undead when it was resuscitated under an Oregon-financed initiative, supported by Governor Kitzaber.

Under the revised Oregon-led finance plan the project budget was estimated to be approximately $2.71 billion. A summary of project revenues is provided (above). Tolls were supposed to cover the $1.9 billion Oregon would have to borrow to build the project — a risk the state would have to bear alone. Here’s a CRC Powerpoint of the failed bridge proposal.

But it was largely all for naught. Or so it would seem.

Columbia River Crossing died a quiet death when, in March, 2014, the Oregon Legislature took no action to keep it going. CRC obituraries are available from the Vancouver Columbian and the Portland Oregonian. The Columbia River Crossing project after more than a decade of work and nearly $190 million in planning, was officially declared dead by the Oregon Department of Transportation in March, 2014.

The Oregon Department of Transportation in 2014 closed the I-5 bridge project’s offices, issued cease-work orders to its many contractors and shut the project down entirely by May 31, 2014.

The Bi-State Bridge Coalition met for the first time in June, 2014, soon after the final collapse of the Columbia River Crossing. The group is led by Clark County Republicans who played a central role in killing off the CRC.

Lots of alternatives have been promoted. “The Common Sense Alternative to the CRC” says it would would achieve the stated goals of the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) freeway and bridge project, but for less money.

Almost all Columbia River vessels come downstream under the center span of the I-5 bridge (no bridge lift necessary). Vessel traffic then veers north to pass through the opening of the BNSF bridge swing span.

According to their video, the “Common Sense” plan would eliminate “95% of the bridge lifts between the I-5 bridge and the BNSF railroad bridge”. That “fact” doesn’t square with my observations of 3 years.

ALL of the hundreds of bridge lifts that I’ve seen are only for clearance of tall barge equipment like cranes, dredges, or tall sailing masts that could NOT clear the high span in the middle of the bridge, as well as routine bridge maintenance, perhaps once a week. The idea that 95% of the bridge lifts could be eliminated is flat wrong. Nearly ALL the bridge lifts are caused by high cargo that won’t fit under the bridge. NOT routine barge traffic.

Building a 2nd lift span on the railroad bridge might be safer and more convenient for barge traffic that currently uses the “S” curve (almost ALL current barge traffic) but it would make NO practical difference in the current number of bridge lifts since most ALL bridge lifts are necessitated by high cargo.

Another (new) proposal for an East County Bridge is championed by Clark County Commissioner Dave Madore, an outspoken opponent of the Columbia River Crossing.

At an estimated $860 million, Madore says a third bridge is a common sense approach to relieving congestion. A fatal CRC flaw, in Madore’s view, was the project’s inclusion of light rail.

His bridge would would connect with SR-14 in Washington, but on the Oregon side it would connect to nothing. It would be located about a mile EAST of the 205 bridge. It would have little impact on current I-5 congestion.

More recently, Seven Southwest Washington legislators came to a consensus and met with their Oregon counterparts in Dec, 2018. In addition to creating a Joint Oregon-Washington Legislative Action Committee, lawmakers in Washington passed legislation that directed the Washington State Department of Transportation to inventory data from prior bridge proposals to expedite the planning process.

The Planning and Sustainability Commission chose the environment over jobs, reports the Portland Tribune. The 2035 Comprehensive Plan Update incorporates The Transportation System Plan (TSP), a 20 year plan to guide transportation investments in Portland.

Portland’s 20-year comprehensive plan map shows it is betting everything on being able to make car-lite transportation dramatically more attractive than it is now.

Portland’s Transportation System Plan (TSP) is aligned with Metro’s Regional Transportation Plan. These comprehensive documents are backed by lots of studies and research.

Oregon legislature in 2017 passed a $5.3 billion transportation package in July 2017, the most comprehensive transportation bill that the Oregon legislature has ever passed.

House Bill 2017, would raise the gas tax by 4 cents in 2018 and then gradually add another 6 cents. Vehicle fees would also increase and there would be another new tax of 0.5 percent on new vehicle sales.

Transit improvements would be funded by a 0.1 percent payroll tax on workers. There would also be additional funding for bicycle and pedestrian paths — and the bill would impose a $15 fee on the sale of adult bicycles that cost at least $200.

Three major Metro-area projects are set up for funding under the plan, and will be funded in part with rush-hour tolls. It would add lanes to Interstate 5 through the Rose Quarter and add lanes to Interstate 205.

Tolls could be an important part of helping to pay for the Portland freeway work, particularly the project to add a lane in each direction on I-205 from the Abernethy Bridge to Stafford Road around Oregon City.

Columbia River Crossing Links:

- Wikipedia: Interstate I-5 Bridge

- Wikipedia: Columbia River Crossing

- ColumbiaRiverCrossing.org

- Oregon Dept of Transportation: CRC

- WS-DOT: CRC

- WA Governor: CRC

- CRCfacts.info

- StopCRC.com

- Oregon Live

- Vancouver Columbian

- Willamette Week

- Bike Portland

- Bike Portland: Common Sense Alternative

- Portland Afoot: Common Sense Alternative

- Dave Madore’s Proposed East County Bridge

- Vintage Portland

- ODOT’s Seismic Report on bridges

Current Columbia River bridge traffic (per day):

- Interstate Bridge 124,000

- Glenn Jackson Bridge 139,000

This Multnomah County page shows the ‘realtime’ status of bridges being open or closed. Portland’s 10 bridges spanning the Willamette River carry 540,000 vehicles per day between them.

- Sellwood 30,000

- Ross Island 55,000

- Marquam 138,000

- Hawthorne 30,000

- Morrison 50,000

- Burnside 40,000

- Steel 25,000

- Broadway 30,000

- Fremont 118,000

- St Johns 23,000

Soon, our cars will drive themselves. That much is clear. Bridges built for cars made in the previous century will not serve needs of the population even ten years in the future.

One alternative that no organization or research group seems to have looked at is rubber-tired people movers that connect the Expo Center to Vancouver. Self-driving people movers are light, fast and cheap.

An expensive bridge is not required. A small, dedicated bridge for autonomous cars, bikes and pedestrians can off-load congestion – providing a light rail alternative without light rail.

Here’s an alternative proposal to reduce congestion. Autonomous shuttles could connect Vancouver to the Yellow Line and completely bypasses freeway congestion. Self driving vehicles will arrive before a new bridge. You can plan on it.

As population grows, mass transit makes sense, especially for dense urban areas. Autonomous vehicles may successfully address the “last mile” problem in the next decade.

Vancouver BC prioritized the movement of people over cars, and it got more people and fewer cars.

The 2018 Regional Transportation Plan sets the course for regional transportation for years into the future. Rethink-X predicts that by 2030, 95 percent of U.S. passenger vehicle miles traveled will be in electric, autonomous vehicles.